Technical Writers in the Development Cycle: Agile vs Waterfall

This article has been kindly reproduced by technicallywriteit.com

Project team members’ grasp of the technical specifics underpinning a project management methodology can sometimes resemble a native speaker’s grasp of grammar. On the surface, it seems more than adequate, but don’t ask them to explain the present perfect continuous.

Waterfall and agile (with its numerous variants, of which scrum is perhaps the most well-known) are two modes of project management that have been dominant in the software industry over the past number of years. (Whether they constitute a process or methodology or something else entirely is not dealt with in this post). If you were to visualise the two approaches on a timeline graph, the waterfall approach would precede agile and be gradually overtaken by it – agile proving the more adaptable option in the IT space.

Here we’ll take a quick look at the defining features of each and then ask how we as technical writers find our roles improved or made more difficult depending on how our projects are governed.

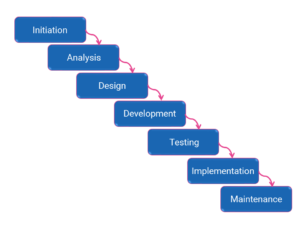

Step by Step: Waterfall

Essentially, this method of project management relies on a sequential process of steps, with each one building on all the previous ones to finally reach the desired end point and delivery of the finished product. When you visualise the waterfall, don’t imagine the single torrent of Niagara but rather the sequential toppling of a waterfall-like the Ebor Falls. In software development, top to bottom typically proceeds through 6-8 steps, for example:

While this approach can work well in cases where there is a very clear and unchanging endpoint in mind, it may be somewhat cumbersome for the fast-changing nature of the software industry. Once your project has begun its path, it is difficult and time-consuming to initiate any deviation from what was originally planned. A significant change may simply mean starting over.

As regards documentation, the waterfall approach can produce a lot of internal content before we get near anything customer-facing: high-level plans, detailed plans, technical specs, architecture graphics, and so on. For technical writers whose main focus is not the internal project documentation but rather the customer-facing elements such as help documents, installation guides, and security guides, there can be a significant lead time between project initiation and availability of raw material. While it may be possible to draw up quality plans, work on the text elements of UI mockups, and investigate requirements during this period, in practice, it can simply mean biding your time.

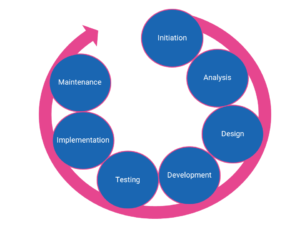

Round and Round: Agile

Agile methodology arose largely in response to the inefficiencies of the waterfall approach. It prioritises iterative development and is well suited to the fluid nature of changing requirements and technologies typical of IT.

Internally, agile strives to produce as little waste as possible. The mounds of files and documents that typify the planning of a waterfall project are done away with in favour of documentation-light short cycles, each one being a mini end in itself. The specifics of how each cycle or module is handled may vary depending on the specific agile practices employed, but the underlying trends are the same. In scrum, a sprint is typically a two-week cycle, at the end of which it should be possible to deploy a working piece of software that addresses the specific backlog items (requirements). At the end of the two-week block, the progress is reviewed and any outstanding requirements may form part of the requirements for the next two-week cycle. During the sprint review and planning processes, it is possible to adapt to changing customer requirements and preferences – there is no final endpoint set in stone. It is also possible to have customer feedback at the end of sprint cycles and incorporate their input in further iterations.

From a documentation point of view, the process can march along in step with development to a greater degree than it could with the traditional waterfall approach. Help documents, videos, and diagrams can be included as specific requirements for a sprint cycle, and their inclusion in a working iteration of software may be considered necessary for that iteration to be complete.

Is Agile the Way Forward?

Apart from the difference in volume and timing outlined above, there are several other differences between waterfall and agile methodologies that affect writers. As the trend is for more teams to opt for an agile approach, let’s take a look at some of its advantages.

Focuses on User-Oriented Tasks

User-friendly and user-centric are adjectives that we would all like to be able to apply to our user assistance content. Working from traditional technical specs, this can involve a lot of battering square pegs into round holes, or a series of emails full of searching questions. With scrum, the backlog items that form the worklist for a single iteration are often presented as ‘user stories’. Immediately, the focus is on what the user needs to accomplish. This is a good first step in creating quality task-oriented documentation.

Promotes Minimalism

The focus of agile processes on ‘just in time’ and ‘just enough’ encourages writers to think along the lines of less being really more. This means that minimalism as a documentation principle lines up very well with the whole agile approach and actively encourages it.

Brings Writers into the Development Team

Small teams working closely together, with daily stand-up meetings and a minimal amount of guiding internal documentation, mean that technical writers may be presented with the perfect opportunity to become an integral part of their development team. The lack of definitive overarching schemas means that the only way to figure out what’s going on is to ask.

Tips for Technical Writers Starting with Agile

Clearly, there are many advantages to agile. However, there are also a few key points that writers should bear in mind when starting to work with teams using this approach.

Manage Time Carefully

While there are rewards to be gained from closer interaction with development, we must also acknowledge that writers are typically assigned to more than one team. It won’t be possible to join every meeting or sprint review call so there is an onus on writers to use careful judgement in how they allocate their time.

Flag Larger Tasks in Advance

While the documentation of backlog items may proceed in step with development, writers may still find themselves faced with a heavy workload towards the end of the development cycle as guides, implementation, and customisation documents need to be produced. To try and avoid this, careful planning needs to be done across the various cycles to divide out the workload in a sensible sequence. Writers need to flag these tasks well in advance to ensure they’re taken into account.

Include Overall Quality Reviews

Each sprint iteration may produce a piece of finished software, but writers must be careful not to overlook the need for an overall review step to ensure accuracy and adherence to standards. The more incremental accretion of documentation should mean that this is a more manageable task than when employing waterfall practices.

Accept Change Gracefully

As iterations progress, we may find that some content is created only to be left aside as the particular aspects of the software are modified or discarded altogether. This can be frustrating, but it is ultimately to the benefit of the user’s experience of the product, and the likelihood is that relatively little effort is actually wasted.

Conclusions From the Real World on Agile vs Waterfall

To put some anecdotal flesh on the bones of the above paragraphs, we asked some of our writers who have experience with both approaches to elaborate on their feelings towards each. The responses suggest that most writers find themselves working more and more in an agile environment:

The reactions were generally positive, but there are occasions when the specifics of a project’s deliverables or timeline mean that agile may not be the most appropriate model. Agile is the preferred option for fast-moving projects with quick turnaround times and some volatility in expectations, and waterfall for longer, more considered and in-depth deliverables:

Illustrating the point with an interesting analogy, one of our colleagues remarked:

In terms of team dynamics and interaction, agile is a clear winner, even when writers and developers are not co-located:

In the end, we can say that the best approach is the one that best suits the combination of team members and project deliverables. An awareness of how our working mode affects our interaction and output is a good first start in finding that sweet spot that comes with good working relationships and achieved milestones. We’d be interested to hear your thoughts about how different modes of work and interaction impact your role as a documentation specialist.