5 Key Skills Every Technical Writer Should Have

This article has been kindly reproduced by techguide.com.au

Technical writers simplify complex, technical information into layman’s terms. But while a thorough understanding of grammar and good writing skills are essential, technical writers require more than that.

In this article, we will discuss the key skills you require to improve your writing and become an excellent technical writer.

Key Skills You Should Have as a Technical Writer

Technical Knowledge

Technical knowledge is a prerequisite for being a good writer in the said niche. During your research, you come across jargon that you must be able to understand or at least look up and comprehend the meaning of. Without a passion for the technical niche, you won’t be able to convey these complex terms in simple words.

For example, a troubleshooting guide about Windows requires specialized knowledge about the software. Similarly, an article about heart surgery needs a thorough understanding of medical terms. Such knowledge can only be developed by spending considerable time studying the subject.

Most technical writers achieve this expertise by niching down. Whether engineering or medicine, writing multiple articles only in a particular niche eventually gives writers authority on the subject. So, while you figure out your niche, you can ask a professional paper writing service to write my essay so that you don’t miss any assignment deadline.

Research Skills

Usually, technical writers aren’t subject matter experts in a given field. However, they develop excellent research skills to write a well-informed article. Good research forms your writing base, especially when the topic is unfamiliar.

Before you begin your research, formulate a framework to decide what information to include. Then, identify the sources of information and organize the data according to the outline.

Though a Google search gives access to lots of information, that shouldn’t be the only component of your research. Technical writing requires accurate information from reliable sources, something conventional search engines might miss.

Instead, browse reports and research papers through Google Scholar, ResearchGate, and other educational databases. And if you have access, it is good to refer to books, whether hard or e-copies. Sometimes, books contain information that isn’t freely available on the internet, especially about technical topics.

However, ensure that all the data is up to date. Topics such as technology and medicine evolve at a fast pace, which means even a year-old article may not be credible on a given date.

Audience Analysis

Analyzing your audience is crucial for the proper presentation of technical information. What age group or professional positions do they belong to? Do they understand technical terms? Understanding the knowledge level of your readers is key to determining the usage of language and words in your writing.

A reader already acquainted with the topic may not need in-depth definitions of all the technical terms. However, a new reader may be confused if you use technical jargon.

Similarly, a product report requires the use of specific terms, while beginner’s guides are best written in layman’s terms. When writing technical articles, you need to ensure that the information is conveyed to the audience at their level of understanding.

Before starting a technical piece, consider your audience’s needs and expectations from the article. For example, do they seek information or solutions? Are they beginners or experts in the field? Do they have any specialized knowledge on the subject?

Answering such questions gives you a brief idea about your target audience and ensures that the article meets their expectations.

Technical Writing Skills

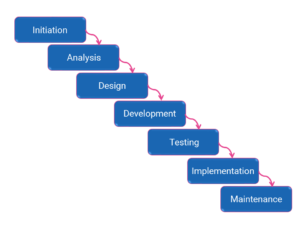

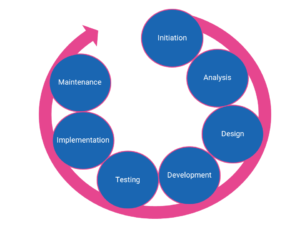

As a technical writer, you need to understand various writing formats, such as user manuals, product reports, etc. While some gigs allow the writers to be creative, most technical projects follow a strict writing format.

For example, a user manual has instructions on how to install or use a product. Similarly, case studies contain information on how a particular problem was solved through the company’s solutions. Each of these has specific writing formats that a technical writer needs to know.

However, all technical writing formats depend on the clarity of the text. A user manual with too many complex terms fails to meet its purpose as the end-user may not understand it. A good technical writer maintains a balance between jargon and simple language while sticking to the boundaries of the writing format.

Usage of Digital Tools

Nowadays, technical writing isn’t only about writing but also about the presentation. And this includes the design and visual representation of the project. As a result, technical writers are expected to be well-versed in using digital tools for writing, designing, and editing.

While all writers use writing tools such as MS Word and Google Docs, you can polish your writing through editing tools like Grammarly and Hemmingway. These tools correct grammar mistakes and increase the readability of your article.

In addition, you also need a basic understanding of Adobe Photoshop and Canva. These tools are helpful for visual designing, which you may require for some of your projects. For example, you can better demonstrate the working of a product by a graphic than by words. In such cases, visual designing skills come in handy.

Ace the Technical Writing

Practice and persistence make a great writer. But what makes them even better is honing their skills. While technical writing is ever-evolving, the above skills are a staple for all writers in this field. With constant practice and a little patience, you can acquire the above skills and master the art of technical writing.